This article originally appeared in The Bar Examiner print edition, March 2015 (Vol. 84, No. 1), pp 4–7.

By Erica Moeser Several years ago I was elected to serve on the Board of Trustees of the small municipality in which I live. I found it striking that often as soon as new residents moved onto one of our Village streets, they began clamoring to have the street turned into a cul-de-sac, or at the very least to have speed bumps the size of small Alps installed to calm the traffic that moved by at the very same pace as when they had purchased their home.

Several years ago I was elected to serve on the Board of Trustees of the small municipality in which I live. I found it striking that often as soon as new residents moved onto one of our Village streets, they began clamoring to have the street turned into a cul-de-sac, or at the very least to have speed bumps the size of small Alps installed to calm the traffic that moved by at the very same pace as when they had purchased their home.

I have recalled that phenomenon over the past few months when thinking of how some legal educators have reacted to the drop in MBE scores earned during the July 2014 test administration. The neighborhood street is lawyer licensing, essentially unchanged, and the cul-de-sac is the wish for the process to change. Some legal educators have expressed hope that NCBE would confess error in the equating of that particular July test. Others have gone further, calling for an overhaul of the test. A few educators (and I treasure them) have pointed out that the test results simply reflect the circumstances in which legal education finds itself these days. It is the very stability of the MBE that has revealed the beginning of what may be a continuing and troubling slide in bar passage in many states.

As I have written previously, my first reaction at seeing the results of the July 2014 MBE was one of concern, and I acted on that concern long before the test results were released. Having nailed down that the results of the MBE equating process were correct, we sent the scores out, and as one jurisdiction after another completed its grading, the impact of the decline in scores became apparent. Not content to rest on the pre-release replications of the results, I continued—and continue—to have the results studied and reproduced at the behest of the NCBE Board, which is itself composed of current and former bar examiners as well as bar admission administrators who are dedicated to doing things correctly.

Legal education commentators have raised questions about the reliability, validity, integrity, and fairness of the test and the processes by which it is created and scored. One dean has announced publicly that he smelled a rat. As perhaps the rat in question, I find it difficult to offer an effective rejoinder. Somehow “I am not a rat” does not get the job done.

The pages of this magazine are replete with explanations of how NCBE examinations are crafted and equated. The purpose of these articles has been to demystify the process and foster transparency. The material we publish, including the material appearing in this column, details the steps that are taken for quality control, and the qualifications of those who draft questions and otherwise contribute to the process. The words in the magazine—and much more—are available on the NCBE website for all those who are willing to take time to look.

The MBE is a good test, but we never rest on our laurels. We are constantly working to make it better. This is evidenced by the fact that the July 2014 MBE had the highest reliability ever of .92 (“reliability” being a term of art in measurement meant to communicate the degree to which an examinee’s score would be likely to remain the same if the examinee were to be tested again with a comparable but different set of questions). The MBE is also a valid test (another measurement term meant to communicate that the content of the test lines up with the purpose for which the test is administered—here the qualification of an entry-level practitioner for a general license to practice in any field of law).

As to the validity of the MBE, and of the palette of four tests that NCBE produces, the selection of test material must be relevant to the purpose to be served, here the testing of new entrants into a licensed profession. The collective judgments of legal educators, judges, and practicing lawyers all contribute to the construction of the test specifications that define possible test coverage. Ultimately a valid and reliable test that is carefully constructed and carefully scored by experts in the field is a fair test.

Those unfamiliar with the job analysis NCBE conducted about three years ago may find it useful to explore by visiting the Publications tab on the NCBE website. At the time of its release, I commended the report to both bar examiners and legal educators because the survey results spoke to the knowledge and skills new lawyers felt to be of value to them as they completed law school and struck out in various practice settings. The job analysis effort was consistent with our emphasis on testing what we believe the new lawyer should know (as opposed to the arcane or the highly complex). Of course, any bar examination lasting a mere two days does no more than sample what an examinee knows. We try to use testing time as efficiently as possible to achieve the broadest possible sampling.

With regard to integrity, either one has earned the trust that comes with years of performance or one hasn’t. Courts and bar examiners have developed trust in the MBE over the 40-plus years it has been administered. Some legal educators have not. Frankly, many legal educators paid little or no attention to the content and scoring of bar examinations until the current exigencies in legal education brought testing for licensure into sharp focus for them.

Of immediate interest to us at NCBE is the result of the introduction of Civil Procedure to the roster of MBE topics that occurred this February. Civil Procedure found its way onto the MBE by the same process of broad consultation that has marked all other changes to our tests as they have evolved. The drafting committee responsible for this test content is fairly characterized as blue-ribbon.

I recognize and appreciate the staggering challenges facing legal education today. I recently heard an estimate that projected Fall 2015 first-year enrollment at 35,000, down from 52,000 only a few years ago. This falloff comes as more law schools are appearing—204 law schools are currently accredited by the American Bar Association, with several more in the pipeline. Managing law school enrollment in this environment is an uphill battle. Couple that with regulatory requirements and the impact of law school rankings, and one wonders why anyone without a streak of masochism would become a law school dean these days. The demands placed on today’s law school deans are enormous.

NCBE welcomes the opportunity to increase communication with legal educators, both to reveal what we know and do, and to better understand the issues and pressures with which they are contending. We want to be as helpful as possible, given our respective roles in the process, in developing the strategies that will equip current and future learners for swift entry into the profession.

Over the past two years, jurisdictions have heeded the call to disclose name-specific information about who passes and who fails the bar examination to the law schools from which examinees graduate. At this writing all but a few states make this information available to law schools. NCBE has offered to transmit the information for jurisdictions that lack the personnel resources to do so. A chart reflecting the current state of disclosures appears below. It updates a chart that appeared in the December 2013 issue.

I am delighted to announce that Kansas has become the 15th state to adopt the Uniform Bar Examination. The Kansas Supreme Court acted this January on a recommendation of the Kansas Board of Law Examiners. The first UBE administration in Kansas will occur in February 2016, and Kansas will begin accepting UBE score transfers in April of this year.

In closing, I would like to reflect on the loss of Scott Street to the bar admissions community. Scott, who served for over 40 years as the Secretary-Treasurer of the Virginia Board of Bar Examiners, was both a founder of, and a mainstay in, the Committee of Bar Admission Administrators, now titled the Council of Bar Admission Administrators. His was an important voice as the job of admissions administrator became professionalized. Scott was selected as a member of the NCBE Board of Trustees and served the organization well in that capacity. He was a leader and a gentleman, and it saddens those of us who knew him to say good-bye.

Summary: Pass/Fail Disclosure of Bar Exam Results

(Updated chart from December 2013 Bar Examiner)

| These jurisdictions automatically disclose name-specific pass/fail information to the law schools from which test-takers graduate. | These jurisdictions automatically disclose name-specific pass/fail information to in-state law schools. Out-of-state law schools must request the information. | These jurisdictions require all law schools to request name-specific pass/fail information. | These jurisdictions provide limited or no disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|

| California, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin | Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota, Mississippi, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Rhode Island, Tennessee, West Virginia, Wyoming | Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Delaware, District of Columbia, Idaho, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, South Carolina |

Disclosure with limitations: Hawaii, New Jersey, Texas No disclosure: Alabama, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Republic of Palau, South Dakota, Virgin Islands |

Hawaii releases passing information only, New Jersey will release information to law schools on request if the applicant executes a waiver; Texas will disclose name-specific pass/fail information on request of the law school unless the applicant has requested that the information not be released; NCBE is currently disseminating name-specific pass/fail information on behalf of Georgia, Iowa, Maine, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, Oregon, and Vermont.

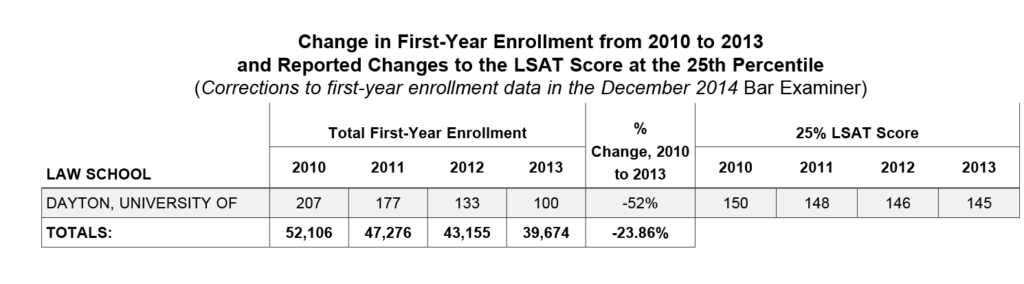

The December 2014 Bar Examiner included a chart showing the change in total first-year enrollment from 2010 to 2013 as provided by the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar and the LSAT 25th percentile for each year. One law school informed us of a discrepancy in need of correction; corrected information appears in the chart below.

Contact us to request a pdf file of the original article as it appeared in the print edition.